Sign In | Starter Of The Day | Tablesmaster | Fun Maths | Maths Map | Topics | More

It seems quite recently that I launched the last newsletter but it has been a whole month. This is the Transum Newsletter for the month of February 2026. What better way to start than with the puzzle of the month.

Percy and Nelly Cod are brother and sister from a large family.

Percy was 19 pence short of the amount needed to buy a badge. Nelly, meanwhile, was just one penny short of affording the same type of badge. They decided to pool their money to buy one badge to share, but even together, they still didn’t have enough.

Here’s what we know about the Cod siblings:

Percy has three times as many sisters as brothers.

Nelly has twice as many sisters as brothers.

How much would it cost Mr and Mrs Cod (Nelly and Percy's parents) to buy badges for all of their children?

If you get an answer, I'd love to hear how you solved the puzzle (or how your students solved it). Fire off an email to: gro.musnarT@rettelsweN

While you think about that, here are some of the key resources added to the Transum website during the last month.

Wrong But Close is a five-level, multiple-choice activity where none of the answers are correct, but one is significantly closer than the others. Students must calculate the actual answer first, then identify which option is nearest. The distractors are based on common misconceptions so students can't just eliminate obviously wrong answers. Progressing from basic multi-digit operations through to complex problems with powers, roots, fractions and percentages, it's an excellent diagnostic tool - when students pick the wrong "close" answer, you can immediately see which misconception led them astray.

PIN Possibilities is a new combinatorics activity in which pupils work out how many different PIN codes are possible under a range of rules and constraints. The questions start with simple cases (such as fixed length codes with or without repeated digits) and then move on to conditions involving parity, palindromes, fixed digits and digit sums. It works well as a quick starter or short practice task, and it provides a clear context for discussing systematic counting strategies.

Decimal Sequences, as the title suggests, requires students to have two key skills to complete these exercises. First, they should be confident adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing decimal numbers. Second, they’ll need to be able to answer questions about arithmetic, geometric and a couple of other sequences.

Distance-Time Graphs can be drawn to represent a wide variety of different situations. You can now find an animal race on the Helicopter View page which is animated and provides a hilarious challenge for your students to draw a graph of the race they see.

This section of the newsletter is called "John Got It Wrong". In my last newsletter I mistakenly gave the 2025 date for Chinese New Year instead of 2026. The correct date is 17 February 2026, and it will be the Year of the Horse. I mention this so that you are aware of some Chinese-themed activities you may like to share with your students as a nod to recognising this international celebration.

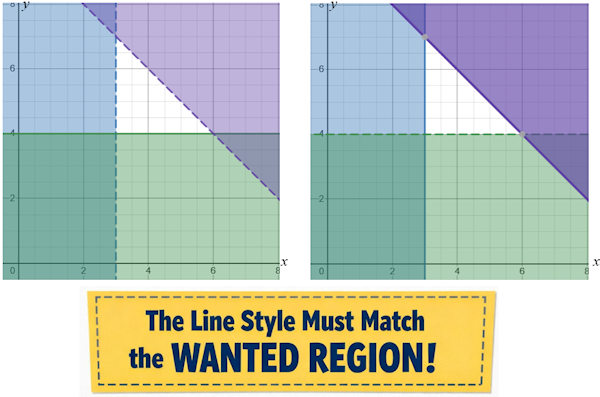

Shading Inequalities questions sometimes ask you to shade the wanted region and sometimes ask you to shade the unwanted region and leave the wanted region unshaded.

Students are often taught that:

However, this can be misleading when the question asks you to shade the unwanted region instead. In that situation, the line style should be chosen to match the region you are actually being asked about. As a rule of thumb: "The line style must correctly describe the boundary of the wanted region."

In a Maths textbook problem, students are asked to randomly choose two numbers and label them x and y.

They were then told that everyone could have Friday afternoon off unless:

Finally they had to show on a graph the region that represents the choices of x and y which resulted in a half-day Friday.

Which of the following two diagrams represents the correct answer?

If students are already proficient using coordinates, an interesting extension is to learn about a variation used in New York. The grid layout of the roads is interesting in itself but did you know that Central Park’s lampposts feature unique 4-digit codes that reveal precise locations within the park. The first two digits (or three digits north of 99th Street) indicate the nearest cross street, such as “67” for 67th Street, while the last two digits denote the side and distance from the edge: even numbers mark the east side near Fifth Avenue, odd numbers the west near Central Park West, with smaller numbers closer to the perimeter and larger ones toward the centre.

Originally designed by Henry Bacon in 1910, these codes helped maintenance crews quickly identify faulty lamps by phone reports, but they’ve since become a clever navigation tool for visitors. Spot a code like 6704 (east side near 67th Street, 4 units from the edge) or 6727 (west side, farther in) to orient yourself without a map. This logical design serves as both a functional tool for city employees and a secret guide for savvy travellers exploring the landscape.

Don't forget that you can listen to this month's podcast which is the audio version of this newsletter. You can find it here, on Spotify or on Apple Podcasts. You can follow Transum on BlueSky, Twitter (some call it X) and 'like' Transum on Facebook.

Dates worth a mention in Maths lessons:

6 February :: Winter Olympics

6 February :: Palindromic Date

14 February :: Valentine’s Day

17 February :: Pancake Day

17 February :: Chinese New Year

Finally the answer to last month's puzzle which was:

My New Year’s resolution is to paint the long fence that goes all the way around Tran Towers. In January I will paint 1/12 of the fence. In February I’ll paint 2/12 of the length of the fence remaining. In March I’ll paint 3/12 of the remaining portion of the fence and so on throughout the year. When during the year will I require the most paint?

(Extension for rocket scientists: what if there were x months in a year instead of 12?)

The answer is March and April. See some methods in the comments below.

The specific version of the original puzzle that I adapted is, I believe, originally from the Junior Mathematical Challenge (JMC), which is part of the United Kingdom Mathematics Trust (UKMT) suite of competitions. I'm not completely sure, however as I have not been able to find it since.

The extension for rocket scientists asked for the solution if there were x months in the year. I am certainly no rocket scientist but research tells me the solution is the nearest month to the square root of x. The square root method falls down when identifying the solution for years that have two months where the lengths are equal.

That's all for now,

John

P.S. I will do algebra, I’ll do trigonometry and I’ll even do statistics, but geometry and graphing are where I draw the line!

Do you have any comments? It is always useful to receive feedback on this newsletter and the resources on this website so that they can be made even more useful for those learning Mathematics anywhere in the world. Click here to enter your comments.

Did you know you can follow this newsletter on Substack completely free of charge? Please note this is separate from a paid subscription to the Transum website, which unlocks a much wider range of premium resources.

Rick, United States

Monday, January 5, 2026

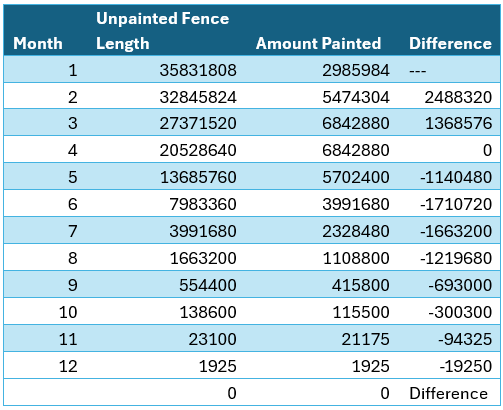

"Rather than deal with fractions, I decided to use excel and a starting length of fence equal to 12^7 so all math would result in integers. The following table has four columns

🛑 Month

🛑 Unpainted fence Length. This is calculated for each row by subtracting the previous month’s unpainted length from the amount painted during that month. The initial length is set to 12^7 for January. This will be sufficient to ensure all calculations will have integer results so no rounding will occur.

🛑 Amount Painted. Equals the Unpainted fence Length times the Month all divided by 12.

🛑 Difference. The difference between what was painted between the current month and the previous month.

Positive numbers represent an increase in amount painted and negative numbers indicate less amount painted. Zero indicates equal parts painted between two months.

From the table, we can observe that for months 3 and 4, each resulted in in the same length of fence painted (6842880) which was the greatest length compared to other months. From a purely mathematical point of view, the most paint was used in both March and April. From a physics point of view, if the fence was in the northern hemisphere, March is colder than April, so the viscosity of the paint would have been thicker, and more paint would have been required in March. "

Kalmakka, Reddit

Thursday, January 8, 2026

"A pattern seems to be that if \(x\) is square, then you do the most work in month \(\sqrt{x}\).

Let us say \(x=n^2\). At the start of month \(n\), \(p\) meters of fence remains.

That means that in month \(n\) we paint \(p\cdot\left(\frac{n}{n^2}\right)=p\cdot\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)\) meters (leaving \(\frac{p(n-1)}{n}\) unpainted).

In month \(n+1\) we paint:

$$ \left(\frac{p(n-1)}{n}\right)\left(\frac{n+1}{n^2}\right) =\frac{p(n+1)(n-1)}{n^3} =\frac{p(n^2-1)}{n^3} <\frac{p}{n}. $$

Since we painted \(\frac{n-1}{n^2}\) portion of the unpainted fence in month \(n-1\), leaving a portion of \(\frac{n^2-n-1}{n^2}\) unpainted, and that this remaining portion equals \(p\) meters, we know that the amount we painted in month \(n-1\) is:

$$ p\cdot\left(\frac{n-1}{n^2-n-1}\right) < p\cdot\left(\frac{n-1}{n^2-n}\right) = p\cdot\left(\frac{1}{n}\right). $$

So we see that in month \(n\) we paint more than in both month \(n-1\) and in month \(n+1\).

If we reason that the function is concave, then this local maximum is also the global maximum.

Whenever \(x=n(n+1)\) we have two maximums, at \(n\) and \(n+1\). E.g. for \(12\) we have that in month \(3\) we paint \(\frac{1}{4}\) of whatever remains, leaving \(\frac{3}{4}\) of that, and in month \(4\) we paint \(\frac{1}{3}\) of that \(\frac{3}{4}\). Since \(\frac{1}{4}=\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\cdot\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)\), we paint the same amount in these two months. "

Edam_Cheese, Reddit

Thursday, January 8, 2026

"A bit of algebraic manipulation gives the amount we paint on the \(n\)th month as \(n\cdot 12^{-n}\cdot(12-1)(12-2)\cdots(12-(n-1))\). I couldn't get the derivatives to work nicely enough to find the maxima from this, so evaluating it for each \(n\) still seems the best way to go.

For the same problem over \(x\) months: I assume that on the \(n\)th month we'll paint \(\frac{n}{x}\) of what remains. So for \(13\) months, we paint \(\frac{1}{13}\)th in Jan, then \(\frac{2}{13}\)th of what's left in Feb, and so on. We can simply swap \(12\) in the above formula for \(x\) to get the expression for the amount we paint on the \(n\)th month, given we take \(x\) months total.

This last part is from inspection of the data, but I can't prove it. For the problem of painting a fence over \(x\) months, we do the most painting on the \(\left\lceil \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{1+4x}-\frac{1}{2}\right\rceil\)th month. When the expression is an integer before taking the ceiling, we also do the same amount of painting on the following month. "

Vidarino, Reddit

Thursday, January 8, 2026

"I poked at this for a bit, and found an algebraic solution, but it's not super-pretty. I think it's correct, though, and should be pretty generalizable. No idea about the source of the problem.

Let \(R_n\) be the amount of work that remains at step \(n\).

It can be expressed as the product of \(\left(1-\frac{k}{12}\right)\) for each \(k\) in \([1,n-1]\). (This can be "algebra-notated" using the product function (capital PI)

Let \(W_n\) be the work for the month \(n\): \(\frac{n}{12}\cdot R_n\).

Since we're only interested in finding out the maximum work, let's compare successive months. This isn't very rigorous, but let's assume that the work done each month first increases and then decreases. To find out when this happens we can solve: \(\frac{W_{n+1}}{W_n}>1\). (I.e. when ratio falls below \(1\) the amount of work starts to decrease.)

Expanding this into all its glory is again quite unsuitable for a Reddit comment field, I'm afraid, but we get a bunch of cancellations, and are left with something that can be simplified to \(\frac{(n+1)(12-n)}{12n}>1\).

Expand and simplify more: \(n^2+n-12<0\).

Factorise: \((n+4)(n-3)<0\).

So by inspection we see that the work ratio increases up until \(n=3\) (at which we can see that it's actually \(0\), so the amount of work will be the same at \(n=4\)).

So, there we go. Hardly elegant, but it is algebraic rather than brute force. "

CyberMonkey314, Reddit

Friday, January 9, 2026

"There's no need for an explicit formula for the amount used in each month to answer the question as stated, or for any differentiation.

Say at the beginning of month \(n\), you have a fraction \(R_n\) of the fence remaining to be painted (so \(R_1=1\), the whole fence). You then paint \(p_n=\frac{nR_n}{12}\) of the fence, so \(R_{n+1}=R_n\left(\frac{12-n}{12}\right) \).

In the next month, you paint \(p_{n+1}=\frac{(n+1)R_{n+1}}{12}\) of the fence. Now, the "trick" is to think about the ratio of the amounts of paint used month on month; i.e. \(\frac{p_{n+1}}{p_n}\).

Substituting in, this is \(\frac{p_{n+1}}{p_n}=\frac{(n+1)(12-n)}{12n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{11-n}{12}\).

Why does this help? When the ratio is greater than \(1\), you've used more paint in month \(n+1\) than in month \(n\). When it's less than \(1\), you've used less. When it is \(1\), you use the same amount. So the maximum amount of paint is used either in the first month \(n\) when \(\frac{p_{n+1}}{p_n}<1\), or it's a tie between months \(n\) and \(n+1\) if \(\frac{p_{n+1}}{p_n}\) is ever exactly \(1\).

Neatly, the quantity \(\frac{1}{n}+\frac{11-n}{12}\) is strictly decreasing! It starts above \(1\) and ends below \(1\). Solving \(\frac{p_{n+1}}{p_n}=1\) leads to \((n+1)(12-n)=12n\), whence \(n=3\) (we ignore the negative solution \(n=-4\)).

Since this solution is an integer, there are two months in which the maximum amount of paint is used, i.e. month \(3\) and month \(4\) (had it not been an integer, a single month would be maximal).

I hope that makes sense (and doesn't have any typos) "